[I saw this film a couple years ago, but never posted a review. I will do so now, for no particular reason. 🙂 ]

I don’t feel fully qualified to review this film, because it’s in Hebrew, which I don’t speak. So I can’t comment on the actors’ delivery of their lines, or even on the script, since I’m basing it off of English subtitles that may not reflect the full meaning.

Even more significantly, Hebrew etymology itself is an important concept in the film, and I can’t be sure to what extent I grasped the word play that goes on. At one point, the narrator alludes to the fact that the Hebrew word for childlessness is related to the word for darkness, which is related to the word for forgetting. This leads me to suspect the title has more meaning in the original. (The film is based on the autobiographical novel of the same name by Israeli author Amos Oz, from which this passage is adapted.)

All that said, I’m going to do my best to review what I can, and let you know when I think my opinions might be colored by my ignorance of the language.

The film is told from the perspective of the young Amos Oz (Amir Tessler) and chronicles his experience growing up in what was then British Mandatory Palestine, which over the course of the film is partitioned by a U.N. Resolution and then falls into civil war.

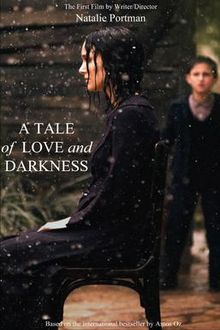

This political element is mostly shown through glimpses and murmurs in the background, since Amos is a young child, and what he perceives first and foremost are incidents in his own family. His father Arieh (Gilad Kanana) and mother Fania (Natalie Portman, who also directed the film and wrote the screenplay) are his main influences. Both are well-educated and, in their own ways, teach him about language and storytelling. His father, a scholarly and bookish man, frequently lectures him about Hebrew words and their interrelated meanings.

Fania is a more romantic type than her husband, and early sequences show her fantasies as a girl growing up in Europe. envisioning Israel as the “land of milk and honey”, to be settled by heroic pioneers. In keeping with her imaginative nature, she tells young Amos stories—some fanciful and fairytale-like, others more depressing and realistic, such as the story from her childhood of a Polish army officer who committed suicide as she watched.

Amos also overhears things he shouldn’t—such as Fania’s mother berating her, causing the younger woman to slap her own face in shame, or Fania telling another grim tale of her youth in Europe: a woman who committed suicide by locking herself in a shed and setting it on fire.

The film shows these scenes, as imagined by young Amos, and you can’t help feeling these aren’t healthy for a child to hear. At the same time, even if you didn’t realize that Oz grows up to be a writer, it becomes very clear in watching the film that this is his calling—everything in his upbringing leads him towards it.

Gradually, as the film wears on and political upheaval takes its toll, Fania begins to succumb to depression. It’s a grim decline, as we see her slowly wasting away, but the film does a good job capturing the pain and frustration seeing a loved one with a mental health disorder brings upon a family. (Even more heart-wrenching is the fact that the doctors prescribe sleeping pills and other depressants—at the time, proper treatment for such disorders was not widely available.)

Fania goes away to her sisters’ home in Tel Aviv, and there overdoses on sleeping pills. In the closing moments of the film, we see Amos as a young man, meeting with his father at a kibbutz. Finally, we see an elderly Amos writing the word “mother” in Hebrew.

The overall film is haunting and evocative, with a gorgeous soundtrack by Nicholas Britell that captures the gloomy mood of Jerusalem, which Oz at one point likens to a black widow.

I did have some issues with the cinematography. It has that washed-out gray/green palette that is way, way overused in films these days—especially those set in the past. I would have preferred to see it in the normal range of colors.

However, while this was a drawback, I did think it very successfully communicated one thing about Jerusalem: its age. Throughout the film, but especially in the shots of the winding, narrow streets that Amos and his family traverse through the city, I could practically feel the weight of all the accumulated history of this ancient place. The film conveyed the mystical power of its setting, and gave a sense of why it is so important to so many.

Again, I don’t want to comment too much on the acting, since I was reading subtitles rather than listening to the speech, but it seemed very good indeed. Tessler is the standout—he had to carry the immense burden of seeming wise beyond his years while still behaving like a normal child, rather than The Boy Who Is Destined To Become A Famous Writer. And he manages it splendidly from what I can tell.

Small moments, like the sequence in which Arieh is celebrating that all five copies of his new book have been purchased, and Amos later sees all five, still in their wrapping paper, at the house of an author Arieh knows (either a friend or relative; I couldn’t tell which), are what stick in my mind. The man simply closes the shelf lid over the books and gives Amos a look that says “we will not speak of this”, without uttering a word.

I went to this film expecting it to be a downer—I knew that it ended with Fania falling into depression and ultimately committing suicide—and for a large part of the second half, it did feel excruciatingly bleak. Watching someone sit silently in the dark, overcome with psychological torment, while her family members suffer in impotent grief, while perhaps true to life, is not a pleasant cinematic experience, and that’s how the film trends for some time. I was ready to write it off as an interesting picture that drowns in mental anguish in the second half.

And then something amazing happened.

I want to write about it, because I haven’t seen many others address it—but I also hate to spoil it. So I’ll make a deal with you: if you haven’t seen the movie, but think you might want to, stop reading now and watch it. Pay particular attention to the scenes of Fania’s stories—the drowning woman, the woman in the shed, the Polish officer. Then come back and read the rest of this. If you’ve already seen it, or just don’t care to but read this far and want to know it all, read on.